SOUTH CARTHAY'S ORIGINS

THE HISTORY OF THE AREA

The Tongva people are the original inhabitants of the land that later included most of Los Angeles, including the central Los Angeles area commonly known today as Mid-City/Mid- Wilshire. In the early 1800s, during the era of Mexican colonization, most of this area was granted to various owners as lands including Rancho Rodeo de las Aguas and Rancho La Cienega. As suggested by their names, these lands had ample water sources and had large areas of wetland that had to be drained and graded for later residential construction. The land that would develop as the three Los Angeles neighborhoods which today are known as Carthay Circle, Carthay Square, and South Carthay sat within the approximately 4,500-acre land grant of Rancho Rodeo de las Aguas. It was granted during the Mexican reign to a woman, Dona Maria Rita Valdez de Villa. Widowed, with three children, she was listed on the deed along with her cousin, Luciano Valdez. Luciano determined to have the grant revoked in his favor, bragging that since “he was a man she was a mere woman he would always win.” Hearing of his boast the “Ilustrissimo Ayuntamierto: “ (Los Angeles City government) came down in her favor and ordered him off the rancho. The U. S. Land commission and the courts confirmed the grant to Maria on June 27, 1871. Subsequent owners eventually sold off parcels of the rancho to a number of other owners who developed the land into today’s Carthay Neighborhoods Historic District, Beverly Hills, and Westwood. By 1881 Los Angeles had grown to its boundaries and the ranchos were being sold off and broken up. We became part of a smaller Rancho, possibly the Whitworth Rancho. There were many other Ranchos in this area, including the La Brea Rancho, Hauser Rancho, and Palms Rancho to name but a few.

The area remained mostly rural until the city’s first population and land boom, which occurred during the late 1880s thanks to the expansion of rail networks and a fare war between the Southern Pacific and Santa Fe Railroads that led to rampant land speculation. During this time, brothers Henry Gaylord and William Wilshire embarked on the development of a grand boulevard free of streetcars that would become the centerpiece of a luxurious residential neighborhood called Westlake. Known as Wilshire Boulevard, the thoroughfare was eventually extended further westward; portions of the route partially comprised an old Spanish-era trail known as El Camino Viejo, or “old road,” that had historically served as the dividing line between Rancho La Brea on the north and Rancho La Cienega on the south.

It ultimately became one of the city’s most iconic east-west commercial corridors, and its development served as the catalyst for growth within the area. Beckoned by the open space and the grand boulevard, Angelenos began shifting westward. With expansion of the city’s streetcar network and street systems making living in Los Angeles’ western suburbs more feasible, residential development in the Wilshire area (some miles east of the Carthay Neighborhoods Historic District) accelerated through the 1910s. Most of the early development came in the form of single-family subdivisions, with apartment buildings occurring on grand scales along Wilshire Boulevard and on smaller scales in other areas. Commercial and institutional development occurred along major streets beyond Wilshire Boulevard, with business districts later emerging along streetcar lines and major streets like Pico Boulevard, Country Club Drive (later W. Olympic Boulevard), La Brea Avenue, W. San Vicente Boulevard (originally Eulalia Avenue), and La Cienega Boulevard.

Los Angeles’s westward expansion accelerated in the early to mid-1920s, when a massive population influx triggered a regional construction boom. It was during this period that substantial development began in the westernmost portion of Los Angeles. The new suburban construction depended on existing transit connections, both electric streetcar lines and newly extended automobile routes. In 1911, Henry Huntington bought and consolidated multiple streetcar companies first established around the turn of the century into his Pacific Electric Railway. The Pacific Electric “red car” system served as a residential subdivision generator and promoter as well as a transportation network, creating and servicing new suburbs all over Los Angeles. By an 1895 court order, the Department of Water and Power could only sell water and power within the city of Los Angeles. Agricultural and oil designated land required less utilities than developing residential areas so it was developers who bought the land and had it annexed to the city. In 1904 the need for water became apparent. The ranchos were broken down further into tracts. Our area was part of the La Brea Annexation. Over the next 40 years tracts were annexed to the city of Los Angeles in return for a guaranteed supply of water. By 1923 there were over 400 of these tracts. Builders descended, designing houses and using the Red, Yellow, and Green railway lines to lure people to these new neighborhoods.

DEVELOPMENT BEGINS

The area known as Carthay was developed by J Harvey McCarthy from whom it takes its name. He was quite a prolific developer and Carthay was his most successful tract. In 1922, 136 acres were purchased by McCarthy who dubbed it “Carthay Center.” His intention was to subdivide it into builders’ lots and to “install high-class improvements, including wide paved streets, parkways, and an ornamental street lighting system.”

McCarthy also planned to build “a shopping center of 18 stores, with parking space nearby, and overlooking ornamental lagoons. In the vicinity of the business center a motion picture theatre was to be erected, as well as a community chapel. Five acres of land were set aside for a school which would be known as the James Frank Burns School, later called the Carthay Center School. He also intended a 100-room hotel, to be called the Ciquatan, which never was built, and that all the buildings would employ the Spanish Mission style of architecture. He assured the success of his 1922 subdivision by convincing Huntington to build an extension of the Pacific Electric’s Santa Monica via Sawtelle line, which connected downtown Los Angeles to points west along Pico Boulevard. The line split into two, running on Venice Boulevard (where it became the Venice Short Line) and Eulalia Avenue (now W. San Vicente Boulevard). From east to west, the new second line crossed the intersections of S. Fairfax Avenue, Country Club Drive, and Eulalia Avenue and from there to a new Carthay Center stop at Eulalia to service the development. McCarthy’s company erected a new stop structure here, in front of Carthay Center’s planned commercial district, in cooperation with Pacific Electric. The streetcar line continued through Beverly Hills to join the Santa Monica Boulevard line, providing a direct connection between the beach cities and downtown Los Angeles. The developers of the Carthay Neighborhoods Historic District often touted their subdivisions’ convenient location equidistant from both places, as well as the ready availability of streetcars and motorbuses to ferry commuters to and from work.

The boom of the 1920s was further facilitated by the rising prominence of the automobile, which opened up outlying areas to suburban development as quickly as the City and private developers could grade roads. Developers and business interests continued to influence the literal direction of automobile development in the service of their new residential and commercial districts, and again J. Harvey McCarthy provided a highly visible example of the results – he worked with the City Planning Commission to approve widening of Wilshire Boulevard and provided most of the funding and manpower needed to accomplish the work in the area of Carthay Center. By April 1924, Wilshire had been graded, widened to 150 feet, and surfaced with concrete between S. Fairfax Avenue and the Beverly Hills city limits. McCarthy also pushed hard to restrict commercial development on Wilshire, envisioning it as a grand residential boulevard bereft of businesses to compete with his projected commercial district, but was unsuccessful. Subsequent improvements on Pico Boulevard, S. Fairfax Avenue, Eulalia Avenue (soon to be known as W. San Vicente Boulevard), and the extension of 10th Street that became Country Club Drive/W. Olympic Boulevard much expanded the area’s street network.

The larger area now containing the Carthay neighborhoods was only sparsely developed until after World War I, with a few residential subdivisions dwarfed by expanses of agricultural land, clusters of derricks pumping from subsurface oil fields, and a small airfield. That all changed in 1922, when the J. Harvey McCarthy Company purchased a large Wilshire Boulevard-fronting tract and began constructing the subdivision of Carthay Center. Thanks to Carthay Center’s successful marketing (and rapid sales), robust transportation networks, and the city’s annexation of more and more land, construction took off in the Mid-City/Mid-Wilshire area. Hundreds of tracts were subdivided and put on the market; they primarily were intended for single-family residences, with larger multi-family properties typically restricted to major arterial streets (though some tracts were developed almost exclusively with small-scale multi-family properties, primarily duplexes in keeping with the area’s predominantly single-family character). Many of the tracts were nameless and comprised only a few blocks, but others boasted bucolic names and larger areas – like Fairfax Park, Olympic-Beverly Plaza, Wilshire Vista, Wilshire Knolls, the residential area of Miracle Mile, and more. Most owed a great debt to Carthay Center, one of the earliest developments in the area, as well as one of the most ambitious and forward-looking.

“CHAPEL TO BE CENTER FOR TRACT” headlined an article in the Los Angeles Times. It stated that Carthay Center’s main founder and developer, J. H. McCarthy, planned to erect an inter-denominational church to honor his mother Amanda. The cost would be $20,000 and it would seat more than 200 people. W. H. Bishop, the architect, envisioned a building that would be an “adaptation of the mission style in reinforced concrete and brick.” It would have hardwood floors, an old fashioned atmosphere, and a belfry rising to a considerable height in which will be hung a bell which formerly called worshippers to services in the early days of the state.” Amanda McCarthy was one of the state’s original pioneers. J. H. was proud of her and the rest of the 49’ers so he named streets such as Commodore Sloat and Shoemaker after them

The fabulous Carthay Circle Theater, with a sculpture in front by Henry Lion of a miner panning for gold was built. Opening in 1926, the Carthay Circle Theater was known for splashy West Coast premieres like “Gone With The Wind”. Disney’s “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” was premiered there in December of 1937 and “Fantasia”, which ran for 45 weeks, had its Los Angeles opening there

A full page ad in the Los Angeles Times announced: “Carthay Center a distinctive home community center in the choicest part of Wilshire’s newer residential area—being scientifically developed by nationally known landscape architects—for persons of moderate means seeking an ideal home environment safeguarded by carefully drawn restrictions—offering convenience, permanence, high investment value, and natural beauty.” Middle class folks arrived on the San Vicente car line to find new Spanish Revival homes priced around $8000

OLYMPIC-BEVERLY PLAZA

(SOUTH CARTHAY) IS BUILT

The Twin Cities Company purchased the approximately 90-acre parcel of land which would become Olympic-Beverly Plaza in 1921 or 1922, around the time this area (along with the Fairfax Park land) was annexed to Los Angeles in February 1922. The parcel was roughly bounded by Country Club Drive (W. Olympic Boulevard) on the north, S. Crescent Heights Boulevard on the east, Pico Boulevard on the south, and La Cienega Boulevard on the west, meaning it directly abutted Carthay Center to the north, Fairfax Park (Carthay Square) to the east, and the Los Angeles city limits to the west and south. Led by president Gerald A. “J.A.” McNulty, Twin Cities was an active participant in late 1920s-early 1930s residential and commercial development in the Wilshire area and subdivided multiple tracts in and around Pico Boulevard and La Cienega Boulevard. The company made a sizable profit selling lots along these burgeoning thoroughfares, mostly within a tract called Beverly Wilshire Terrace, and also constructed some buildings for lease itself.

One notable result of a Twin Cities sale was construction of a large, Spanish Colonial Revival Ralph’s Market and warehouse building in 1931 on the north side of Pico just east of La Cienega. The developer appears to have had other dealings with the Ralph’s Grocery Company, as the market leased much of the land that would later be subdivided into Olympic- Beverly Plaza and used it to grow produce. Twin Cities leased the southwestern portion of its 90-acre holding to the Pico Fairway golf driving range from 1929 until 1933, when it finally subdivided the land it had held for over a decade. The reasons for the company’s wait to develop this area are unknown.

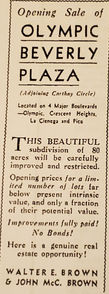

McNulty subdivided the land as Tracts 8109, 10733, and 10756 in 1933 and announced the opening of the first unit of his new Olympic-Beverly Plaza Tract in July 1933. As the surrounding areas had been developing since 1922, the new tract represented a rare opportunity or infill development within the established, and highly desirable, Carthay area. Contrary to the general perception of a construction halt during the Great Depression, building continued across Los Angeles at a steady rate during this time, and Olympic-Beverly Plaza was no exception. The developer’s sales agents advertised the tract as the last chance to buy lots directly adjoining Carthay Circle (and did call it Carthay Circle, not Center), and made clear it would carry similar restrictive covenants to ensure quality and homogeneity – the new tract was to be “carefully improved and restricted.” Like Fairfax Park’s, Olympic-Beverly Plaza’s advertisements also emphasized proximity to major thoroughfares – W. Olympic Boulevard, S. Crescent Heights Boulevard, La Cienega Boulevard, and Pico Boulevard – all of which had been widened, paved, and otherwise improved since the development of the area’s 1920s subdivisions. Access to streetcar lines was less of a selling point than it had been a decade earlier, and public transit opportunities were not highlighted in the ads.

The new tract evoked Carthay Center in its wide streets, concrete sidewalks and curbs, streetlights, strict restrictions, and most prominently through the layout of its streets and blocks. Its east and west portions followed the slightly skewed, regular street grid like the streets of Fairfax Park and featured long, north/south-running blocks. These outer portions flanked a triangular central portion which tapered to a point at its southern end and contained north and south-facing buildings on Olympic Place and W. Whitworth Drive, running perpendicularly to the rest of the streets here. This served to slow traffic and turn focus inward toward the center of the development, while facilitating entry from Pico Boulevard as well as W. Olympic Boulevard. Olympic-Beverly Plaza reserved the lots in and around the narrowest part of the central triangle for multi-family development, along with lots along the busier streets at the periphery of the subdivision.

This resulted in dense and consistent development of two-story multi-family buildings, predominantly duplexes, along W. Olympic Boulevard, S. Crescent Heights Boulevard, and the “Y” formed by S. La Jolla Avenue and S. Orlando Avenue. Olympic-Beverly Park’s close relationship with the adjoining Fairfax Park is illustrated by the consistency of properties on South Crescent Heights Boulevard – though the west side is in the 1933 tract, while the east side is in the 1923 tract, they are indistinguishable. Multi-family residences are also scattered throughout Olympic-Beverly Park in smaller numbers, leaving S. Alvira Street and Olympic Place as the only two streets composed entirely of single-family residences. As in both Carthay Circle and Fairfax Park, Olympic-Beverly Plaza’s architectural designs for both single- family and multi-family residences were overwhelmingly Spanish Colonial Revival. Minimal Traditional and French Renaissance Revival designs are more common than in the adjacent subdivisions, reflecting both the later development period of this tract and the utility of both of these styles for multi-family designs.

Olympic-Beverly Plaza’s developer established a sales office in a Craftsman cottage at the northeast corner of La Cienega and Pico, on a lot it probably already owned. Twin Cities started by erecting model homes in order to attract buyers. The first, a Spanish Colonial Revival duplex, was actually underway when the developer announced the opening of the tract. A larger group of nine duplexes and 17 single-family residences followed in January 1934 and were open for visitation by February; a newspaper display ad called for buyers to: See this group of charming, new single dwellings in the rapidly-growing district the entire city of Los Angeles is watching with interest. Brand-new designs, sturdy construction, all late features, and, most surprising of all, unusually low in price. On exhibition also, new model 2-story duplex residences...homes with income. McNulty appears to have worked with a number of builders in the model home effort, who erected both single-family and multi-family buildings. The model homes were designed in a range of architectural styles, but Spanish Colonial Revival designs were dominant and soon cam to be the definitive idiom of Olympic-Beverly Plaza. Confirmed examples of model homes in the tract, clustered in its northeast portion, include duplexes like 1025-1027 S. Crescent Heights as well as single-family residences like 6500 and 6501 W. Whitworth Drive. The model homes were quickly joined by more buildings as owner-developers bought up lots, often in contiguous stretches along one or more adjacent streets (in a pattern following that seen in Fairfax Park),and commenced construction.

As in Fairfax Park, numerous owner-developers worked in the subdivision, with some, like H.H. Trott, Adolph Horowitz, and Joe Eudemiller, constructing dozens of properties. By far the most prolific, though, was Spiros George (S.G.) Ponty, who constructed at least 64 homes in the tract between 1934 and 1938. They were predominantly Spanish Colonial Revival single-family residences constructed in groupings along S. Alfred Street, S. Orlando Avenue, and S. Alvira Street. Ponty prided himself on the quality of his work and the variety of his designs – working mostly with architect Alan Ruoff, Ponty erected his many Olympic-Beverly Plaza homes without repeating any designs. The consistent Ponty-built stretches of one-story, Spanish Colonial Revival homes are what most Angelenos think of when they think of South Carthay.Development in the tract continued steadily through the 1930s, and by the end of the decade Olympic-Beverly Plaza was almost totally built out. The handful of new buildings constructed in the 1940s and early 1950s continued the same architectural styles and scales as the 1930s buildings. The tract, now known as South Carthay for its longtime association with Carthay Circle, has retained its historic character and was locally designated as a Los Angeles Historic Preservation Overlay Zone in 1984.

SPIROS PONTY

Spiros George (S.G.) Ponty was the most prolific builder in the entire Carthay Neighborhoods Historic District, constructing at least 70 residences across the three neighborhoods from 1933-38. The majority of Ponty’s constructions were concentrated in Olympic-Beverly Plaza (South Carthay) on blocks of S. Alfred Street, S. Orlando Avenue, and S. Alvira Street. Ponty often worked with developer-owners (including Substantial Homes Ltd. and his own company Ponty & Miller Ltd.) as well as individual owners. Designs were most often expressed in one-story single-family residences, primarily in Spanish Colonial Revival or Minimal Traditional styles. Spiros (sometimes alternately spelled Spyros) Ponty immigrated to the United States from Greece in 1916 and started a building career in Los Angeles in 1929. He constructed thousands of homes across Los Angeles, ranging from modest to elaborate, in areas such Westwood, Norwalk, Beverly Hills, and the San Fernando Valley. In the post-war period, Ponty focused on designing dignified yet affordable houses for returning veterans and their families. The elegant and individually unique designs in the Carthay Neighborhoods Historic District represent some of the best-known work of the productive builder’s lengthy career.Architect names rarely appear on building permits for Ponty’s projects, though it is known that in South Carthay he worked closely with architect Allen K. Ruoff – Ponty would create his own sketches based on client requests, then take them to Ruoff for integration into the exterior designs.

If the majority of Ponty’s 70 Carthay houses (64 of which are in South Carthay) were indeed designed by Ruoff, he would have been the most prolific architect in the district, designing more buildings than the Horatio W. Bishop staff. Ruoff was born in Texas in 1894 and moved to Los Angeles sometime before 1910, where he worked as an art director for motion pictures before becoming an architect. By 1923, he had opened his own practice in partnership with Arthur C. Munson and soon began publishing articles on home design in the Los Angeles Times. Ruoff was well known for his Period Revival single-family residences, executed on various scales; he worked with developers as well as individual homeowners, including the Lincoln Mortgage Company and S.G. Ponty. He also completed at least one institutional design, or the Mediterranean Revival Wilshire branch of the Los Angeles Public Library (149 N. St. Andrews Place, 1927). This building was listed in the National Register in 1987

Other local contractors contributed residences to the South Carthay area. Monroe Horowitz is listed as the contractor for 20 of the residences. H. H. Trott is listed as the contractor for 15 of them. Other local contractors each contributing from approximately six to twelve residences include Max Weiss, Paul Harter, Oscar Kalish, W. H. Mandler, J. C. Renton, the Ley Brothers, M. Burgbacher & Sons, R. R. Pollock, and T. C. Bowles. The single family residences were constructed primarily between 1932 and 1936. The cost of a typical one story, one family, seven room residence was approximately $4,800.

A Photo Gallery of Our Area